Celebrating 5 fun-filled years of rattlesnake research in the Physiological Ecology of Reptiles Laboratory at Cal Poly! In this post, I want to introduce you to some of the cool things we have seen rattlesnakes doing, and to the students who have made it all happen.

Celebrating 5 fun-filled years of rattlesnake research in the Physiological Ecology of Reptiles Laboratory at Cal Poly! In this post, I want to introduce you to some of the cool things we have seen rattlesnakes doing, and to the students who have made it all happen.

We do not keep a colony of rattlesnakes at Cal Poly. We only keep rattlesnakes in captivity for short periods of time while they are outfitted with radiotransmitters for our research on their physiology and behavior. The students spend most of their quality time with the snakes not in the lab, but in the field.

We do not keep a colony of rattlesnakes at Cal Poly. We only keep rattlesnakes in captivity for short periods of time while they are outfitted with radiotransmitters for our research on their physiology and behavior. The students spend most of their quality time with the snakes not in the lab, but in the field.

One of the great things about studying rattlesnakes is that they are large enough that we can insert a Holohil Systems 13-gram radiotransmitter (about half the width and length of a tube of lipstick) into the snake's body cavity. The battery last for two years, allowing us to track the same snake for extended periods without multiple surgeries.

To anesthetize the snake, it is gassed with isoflurane in a plastic tube (all surgery photos by M. Feldner):

Then a small incision into the body cavity is made, and the sterilized radiotransmitter is inserted:

Then a small incision into the body cavity is made, and the sterilized radiotransmitter is inserted:

We also insert a Thermochron iButton datalogger, which collects data on the snake's internal body temperature at whatever intervals you like (usually every 1-2 hours in our studies):

We also insert a Thermochron iButton datalogger, which collects data on the snake's internal body temperature at whatever intervals you like (usually every 1-2 hours in our studies):

All sutured up:

All sutured up:

To wake the snake up, a tracheal tube is inserted into its glottis:

To wake the snake up, a tracheal tube is inserted into its glottis:

Then I blow into the tube to inflate the snake's lung with air, so when the air comes out, so does the isoflurane, and snake wakes up.

Then I blow into the tube to inflate the snake's lung with air, so when the air comes out, so does the isoflurane, and snake wakes up.

Then the snakes are returned to the field site and can be radiotracked to locate them as often as you want, to get data on behaviors, movement, etc., or to collect the snakes for blood sampling. Here is Kyle, one of the first students to work on snakes with me at Cal poly (2007). (Incidentally, Kyle couldn't stay away and is beginning his graduate work with me next month... on lizards!)

Then the snakes are returned to the field site and can be radiotracked to locate them as often as you want, to get data on behaviors, movement, etc., or to collect the snakes for blood sampling. Here is Kyle, one of the first students to work on snakes with me at Cal poly (2007). (Incidentally, Kyle couldn't stay away and is beginning his graduate work with me next month... on lizards!)

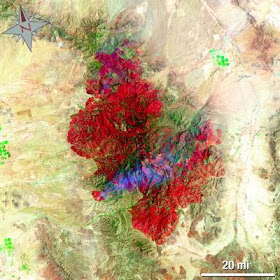

Our field site is the Chimineas Ranch unit of the Carrizo Plain Ecological Reserve. This is a ~30,000 acre ranch that is managed for cattle, game, and wildlife. Its northern edge is studded with water impoundments and rocky outcrops that comprise perfect rattlesnake habitat:

Our field site is the Chimineas Ranch unit of the Carrizo Plain Ecological Reserve. This is a ~30,000 acre ranch that is managed for cattle, game, and wildlife. Its northern edge is studded with water impoundments and rocky outcrops that comprise perfect rattlesnake habitat:

The ranch also has a beautiful house with pool and hot tub that you can rent while you do research.

The ranch also has a beautiful house with pool and hot tub that you can rent while you do research.

Current graduate student Tony in the poolside cookhouse:

Current graduate student Tony in the poolside cookhouse:

The past five years of research on this species, the northern Pacific rattlesnake, have yielded all sorts of interesting natural history data. A very common sight in the spring (also in the fall, but less so) is courting rattlesnakes. Males coil next to or on top of a female, and run their chins all over the female's back in the hopes that she will become receptive to his advances. Males often stay with females for prolonged periods of time.

The past five years of research on this species, the northern Pacific rattlesnake, have yielded all sorts of interesting natural history data. A very common sight in the spring (also in the fall, but less so) is courting rattlesnakes. Males coil next to or on top of a female, and run their chins all over the female's back in the hopes that she will become receptive to his advances. Males often stay with females for prolonged periods of time.

In the late spring the rattlesnakes are commonly found with food bulges that are suspiciously similar in size to a juvenile ground squirrel:

In the late spring the rattlesnakes are commonly found with food bulges that are suspiciously similar in size to a juvenile ground squirrel:

Sometimes we are lucky enough to witness the feeding events itself. Recently graduated grad student Matt (now off to start his PhD studying venom ecology at Ohio State) took this photo of a snake mowing a kangaroo rat.

Sometimes we are lucky enough to witness the feeding events itself. Recently graduated grad student Matt (now off to start his PhD studying venom ecology at Ohio State) took this photo of a snake mowing a kangaroo rat.

Another snake eating a kangaroo rat, this time on the ranch house grounds (photo by J. Ahle):

Another snake eating a kangaroo rat, this time on the ranch house grounds (photo by J. Ahle):

Here is one of our radiotagged snakes eating a bird. We didn't get close enough for a positive ID on the bird for fear of disturbing the snake, but it might be a cowbird or blackbird:

Here is one of our radiotagged snakes eating a bird. We didn't get close enough for a positive ID on the bird for fear of disturbing the snake, but it might be a cowbird or blackbird:

Rarely, we found the predator becoming prey. Here, an adult California kingsnake is constricting an adult female rattlesnake (photo by M. Feldner):

Rarely, we found the predator becoming prey. Here, an adult California kingsnake is constricting an adult female rattlesnake (photo by M. Feldner):

We strive to make our activities accessible to as many people as possible, to demystify rattlesnakes and show the public how docile and beautiful rattlesnakes are in their natural habitats. We bring groups of students from Cal Poly's Wildlife Club, Herpetology class, etc. to the ranch to see the herps. Here Tony is allowing students to touch a safely restrained rattlesnake.

We strive to make our activities accessible to as many people as possible, to demystify rattlesnakes and show the public how docile and beautiful rattlesnakes are in their natural habitats. We bring groups of students from Cal Poly's Wildlife Club, Herpetology class, etc. to the ranch to see the herps. Here Tony is allowing students to touch a safely restrained rattlesnake.

Jordan was an undergraduate studying thermal biology of the rattlesnakes (2009):

Jordan was an undergraduate studying thermal biology of the rattlesnakes (2009):

Bree did her undergraduate research project with me in 2009 on rattlesnake spatial ecology, and is now getting her PhD studying rattlesnake-rodent behavioral interactions (You can read her blog here).

Bree did her undergraduate research project with me in 2009 on rattlesnake spatial ecology, and is now getting her PhD studying rattlesnake-rodent behavioral interactions (You can read her blog here).

Peter (left) and Craig were respectively undergraduate and graduate students doing some of the earliest work on rattlesnakes in my lab (2007-2008). Craig is now pursuing his PhD studying physiology of timber rattlesnakes at the University of Arkansas.

Peter (left) and Craig were respectively undergraduate and graduate students doing some of the earliest work on rattlesnakes in my lab (2007-2008). Craig is now pursuing his PhD studying physiology of timber rattlesnakes at the University of Arkansas.

Vince, a community college student doing research on snake brains in my colleague Christy Strand's lab, came out for a chance to hold one of his study animals (2010):

Vince, a community college student doing research on snake brains in my colleague Christy Strand's lab, came out for a chance to hold one of his study animals (2010):

Those pair-bonded to the PI also get a chance, especially when he finds 75% of the snakes in a given day. Here's Steve holding his first rattlesnake (2010):

Those pair-bonded to the PI also get a chance, especially when he finds 75% of the snakes in a given day. Here's Steve holding his first rattlesnake (2010):

Other than outreach, why are we actually holding rattlesnakes? Because our research questions often require us to collect blood samples to measure hormone concentrations, lending us the dubious titles of Snake Vampires. Here, current undergraduate Scott (left) and Tony take a blood sample from the caudal vein of a snake:

Other than outreach, why are we actually holding rattlesnakes? Because our research questions often require us to collect blood samples to measure hormone concentrations, lending us the dubious titles of Snake Vampires. Here, current undergraduate Scott (left) and Tony take a blood sample from the caudal vein of a snake:

On another day, Tony and Matt take a sample:

On another day, Tony and Matt take a sample:

You can read more about PERL's rattlesnake research at our website and publication site. Look for more coming soon as all the boys (and Bree gal) publish their stuff!

You can read more about PERL's rattlesnake research at our website and publication site. Look for more coming soon as all the boys (and Bree gal) publish their stuff!